The meat and potatoes of the GNU's mandate

Can the poor afford to eat in this economy?

Happy New Year and welcome to 2025: a defining year for the Government of National Unity (GNU) and its main protagonists, the ANC and the DA.

With the 2026 local government elections shaping up to be a mid-term referendum on the GNU, 2025 is the year when South Africans need to feel some tangible benefit arising from the Government’s performance. The GNU can no longer sustain itself on good vibes alone . A good SONA and solid Budget next month won’t cut it: South Africans have heard enough about plans, committees, dialogues and clearing houses. Delivery needs to happen and yes, it’s the economy stupid – can more jobs be created and then critically, how easy will it be for South Africans to put food on the table?

The issue of political stability will remain top of mind throughout this year as the question of whether the GNU will hold gets asked time and time again. The coalition ended 2024 on terra firma with consensus reached on the BELA bill, enabling President Cyril Ramaphosa to sign the act into law without any amendments.

It is likely that the GNU will survive the year., despite Paul Mashatile joining the SACP conference late last year in singing “Asiyifuni GNU” (we don’t want the GNU), the opposition of the Gauteng ANC, SACP and COSATU as well as the tricky policy issues of the NHI and future of the SABC, the consequences of the GNU failing are far too great for the ANC and DA. That may change as the gloves come off ahead of the local government election and ahead of the ANC National Conference in 2027. But for now, the benefits of being in the coalition outweigh the pain.

The question that will be at the forefront of both the ANC and DA’s mind as they gaze beyond 2025 is what they will have to show for two years and more of GNU governance when the posters start hitting the poles in Metros and municipalities across the country next year.

The greatest threats to political stability and voter satisfaction are high inflation and a crippling unemployment rate. Middle-class households are clearly under pressure based on the recent two-pot withdrawals from Discovery and Old Mutual.

If people with jobs and savings are feeling the pinch, how much worse are things for the bottom 30%, the households dependent on social grants and informal jobs to survive? Has the taming of consumer price inflation (CPI) made life any easier for poor South Africans?

Our review of inflation trends confirms that monetary policy and inflation targeting does not benefit poor South Africans. We need new ideas and tools to address the food price inflation that traps many households in poverty.

For the last 18 months, headline inflation has been within the Reserve Bank’s target of between 3% and 6% - it even undershot the 3% lower band in recent months.You would think that this would be cause for celebration but the gap between the official rate and the reality for low-income households is wide.

The graph below tracks headline inflation from January 2009. South Africa introduced inflation targeting in February 2000 and has done moderately well at keeping inflation within the targeted range of 3% to 6%. There have been periods of high inflation (most of 2008 and 2009, all of 2016 and the first quarter of 2017, and from May 2022 to May 2023) but the overall picture is good.

Unfortunately, just like many other averages and means, the official inflation rate has little bearing on the budgets of poor South Africans. StatsSA also calculates the price increases by expenditure decile, meaning that each 10% slice of South African households faces a different inflation rate - sometimes significantly different.

The graph below shows the inflation rate for each decile from Decile 1, the poorest 10% of households (in red), to Decile 10, the richest 10% of households (in blue). Richer households experience an inflation rate similar to the headline inflation rate while poorer households must deal with inflation rates that peak much higher and dip far lower.

For example, when headline inflation peaked in March 2009 at 8.5% it was above 12.5% for the poorest 40% of households. While headline inflation averaged 6.3% between January 2016 and March 2017, inflation was over 8% for the poorest 40% and over 8.3% for the poorest 20%. And, when headline inflation averaged 7.2% from May 2022 to May 2023, it averaged over 9.5% for the poorest 20%.

When official inflation spikes above the 6% target, poorer households also face far higher prices for longer. The poorest 30% of households had a sustained period of high prices from mid-2011 to mid-2013, a period of unremarkable headline inflation. The poorest 10% of households had to deal with higher prices from mid-2021, a full nine months before headline inflation breached the 6% mark, and their inflation rate only dipped back below 6% in the last six months.

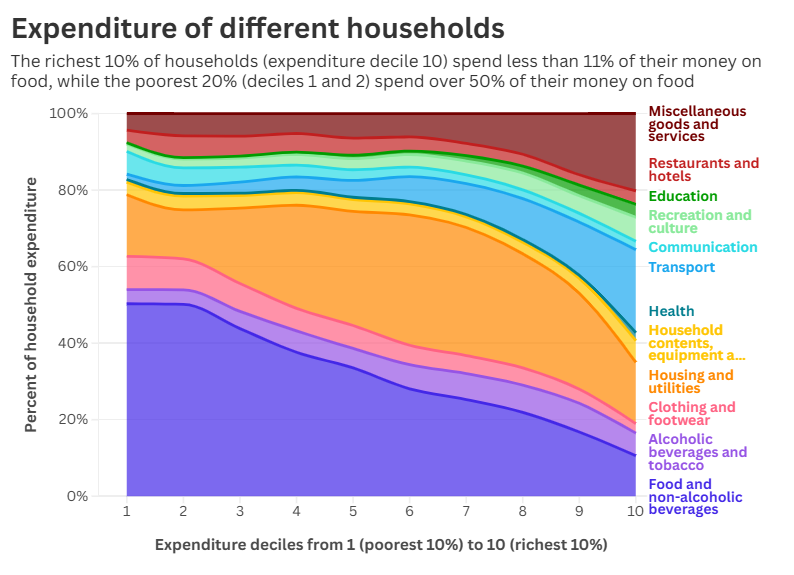

Different households experience different inflation rates because of their different consumption patterns, particularly the consumption of food and non-alcoholic beverages. StatsSA published its updated calculations of CPI in January 2022 and the graph below shows how consumption varies for different households.

Food is the most important purchase for half the country (deciles 1 to 5). The poorest 20% of households spend over half of their money on food and the next poorest 30% spend at least a third of their money on food. Housing-related expenses (rent, bonds, and utilities) is the biggest spending item for deciles 6 to 9 while the richest 10% of households spend the most on transport and other services.

Food inflation is much more volatile than most other price increases. It is also resistant to the blunt tools of macroeconomic monetary policy; food prices increases are mainly due to supply constraints while the Reserve Bank focuses on dampening demand through higher interest rates.

The graph below shows the contrast between food inflation and headline inflation. It also shows the strong link between food inflation and the inflation rate experienced by the poorest 30% of households.

When food inflation spikes it drags the inflation rate up for the poorest households. There is not much that a food-insecure household can do when the price of half of its consumption basket increases by over 10%; it can’t cut food consumption and most of the other goods it purchases are also essentials like rent, clothing and utilities.

The energy and food supply shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic led to two years of global inflation. Tighter monetary policy has not helped poor households recover from double-digit food inflation and it will be of no assistance to them when the next food supply shock comes.

As is par for the course in South Africa, we expect our macroeconomic policies and institutions (including National Treasury and the Reserve Bank) to do the heavy lifting while we give a free pass to the government departments that should be fixing our microeconomic problems. The department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, together with the departments of Public Enterprise, Transport, and others must work together to prioritise food production and distribution.

For the first time in our democracy we have a minister of Agriculture and Rural Development - and a Gauteng MEC - not from the ANC. There is an opportunity to tackle food security at the household level and break the cycle of poverty, if ministers from different parties work together in a true spirit of unity. Easing the burden of poor families would be a tangible benefit of the GNU and could boost both the ANC and DA ahead of the next election. Could our politicians dare to be brave for the country’s benefit?